Skateboard Research

PUSH TO HEAL: PILOT PROJECT

Final Evaluative Report Prepared for Hull Services

January 28, 2022

Overview

The Push To Heal skateboarding program at Hull Services began in 2015 when Hull Services received community donations to create the Matt Banister Memorial Skatepark. The skateboarding program at Hull Services is unique because it incorporates psychoeducation using the Neurosequential Model of Therapeutics (NMT). The NMT is specifically designed to help youth affected by maltreatment. Since trauma stunts brain development in unique ways, unique approaches are required to heal the traumatized brain (Perry, 2009). The NMT is one of the only approaches that has empirical evidence to demonstrate its effectiveness among youth in foster care and adoptive care (Zarnegar et al., 2016). The NMT is not a therapy; it is an approach that integrates core principles of neurodevelopment and traumatology to inform work with children, families and the communities in which they live. The NMT approach, along with the vast majority of psychotherapy programs, are difficult to evaluate in this uniquely vulnerable population, which leads to a critical knowledge gap since evidence shows that youth in foster care do not respond to psychotherapies that are effective in the general population (Bellamy et al., 2010; Hambrick et al., 2016).

Children exposed to maltreatment have worse physical and mental health throughout their lifespan and are more prone to obesity and sedentary lifestyles (Copeland et al., 2018; Felitti et al., 1998; Flaherty et al., 2009). Participating in team sports and group activities partially protects against the negative effects of child maltreatment, likely through the combination of exercise and social bonding (Easterlin et al., 2019; Eime et al., 2013). Unfortunately, kids who experience maltreatment are less likely to participate in activities with other youth, including sports (Easterlin et al., 2019). There is a need to identify group sporting activities that are highly engaging to youth affected by child maltreatment to improve their long-term physical and mental health outcomes.

Skateboarding synergizes with the NMT since a core component of the NMT is increasing emotion regulation through rhythmic activation of the body’s sensory system and motor system (Perry, 2009), which occurs when learning to ride a skateboard and perform tricks. Indeed, there is also evidence that, among adolescents, combining psychotherapy with pleasurable physical activity enhances the beneficial effects of psychotherapy (Warner et al., 2014). Thus, Hull Services’ unique combination of skateboarding and the NMT is precisely calibrated to improve the mental and physical health of their clients who are impacted by child maltreatment.

Although there is anecdotal evidence from Hull Services to suggest skateboarding has a positive impact on the mental health of youth, there is a lack of research to support this relationship. To build knowledge around the potential relationship between skateboarding and youth mental health, the purpose of this study was to evaluate the effectiveness of a pilot project at Hull Services that combined skateboarding and NMT for youth affected by maltreatment.

Methods

Participants

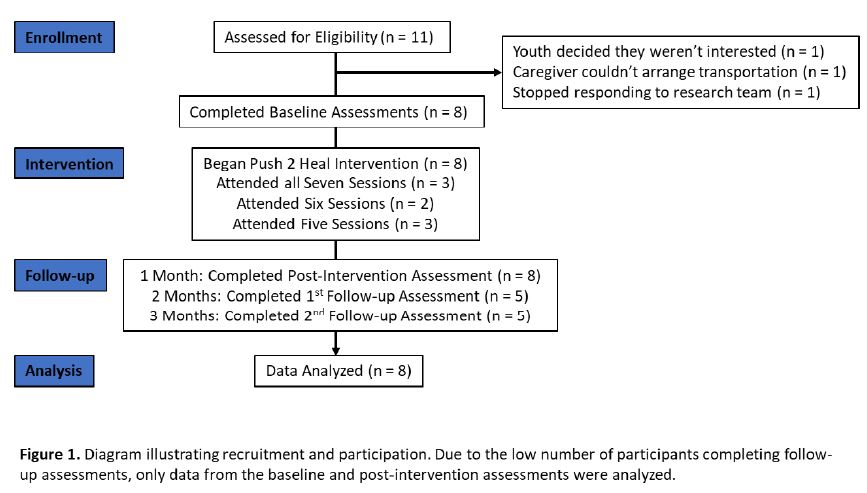

In total, eight youth participated in this study. Potential participants were identified through Hull Services staff. Emails were sent to potential participants by the research team in which the study was explained, eligibility requirements were confirmed, and the informed consent process began. Participants were given $70 for completing all assessments.

Intervention

Participants attended six, 2-hour sessions, twice per week from July 20, 2021, to August 5, 2021. Each session began with 15 minutes of NMT content, followed by 90 minutes of skateboarding content, and ended with another 15 minutes of NMT content. Participants were provided with a skateboard and all safety equipment which they were allowed to keep once the intervention ended.

The NMT content was split into seven different lessons as follows:

- Lesson 1: Physical Safety: Why does it matter that we feel safe?

- Lesson 2: Environmental Safety: What about the surrounding environmental communicates that we are safe?

- Lesson 3: Sensation: How do senses enter our brains? How do we use our senses whiles skateboarding? How does skateboarding make our body feel?

- Lesson 4: Stress Response: How do our senses trigger the body’s stress response? How do we behave when we are stressed? How can we use activities like skateboarding to calm ourselves down?

- Lesson 5: Rewards: How does our brain reward us for doing certain things? What are the short- and long-term effects of seeking easy rewards (like food or drugs) versus seeking harder rewards (like physical or social activity)?

- Lesson 6: Plasticity and Problem Solving: Why is it hard to think clearly and solve problems when we are stressed? How can we use brain plasticity to learn new ways of responding to stressful situations?

- Lesson 7: Final Summary & Reflection: What self-regulation skills have you learned? How will you use these skills going forward?

The skateboarding content was split into seven different lessons as follows:

- Lesson 1: Intro to skateboards and equipment. Foot Position. Skate Game “Flip Deck”

- Lesson 2: Skatepark Terminology and Etiquette. Pushing. Skate Game “Red Light, Green Light”

- Lesson 3: Pushing. Tic-Tacs. Skate Game “Cone Relay”

- Lesson 4: Carving. Ollie. Skate Game “Limbo”

- Lesson 5: Rolling in. Dropping in. Skate Game “Follow the Leader”

- Lesson 6: Flip Tricks. Grinds. Skate Game “Invent a Trick”

- Lesson 7: Skate Game “Relay Race”. Hand out gear to keep.

Data Collection

Quantitative Data

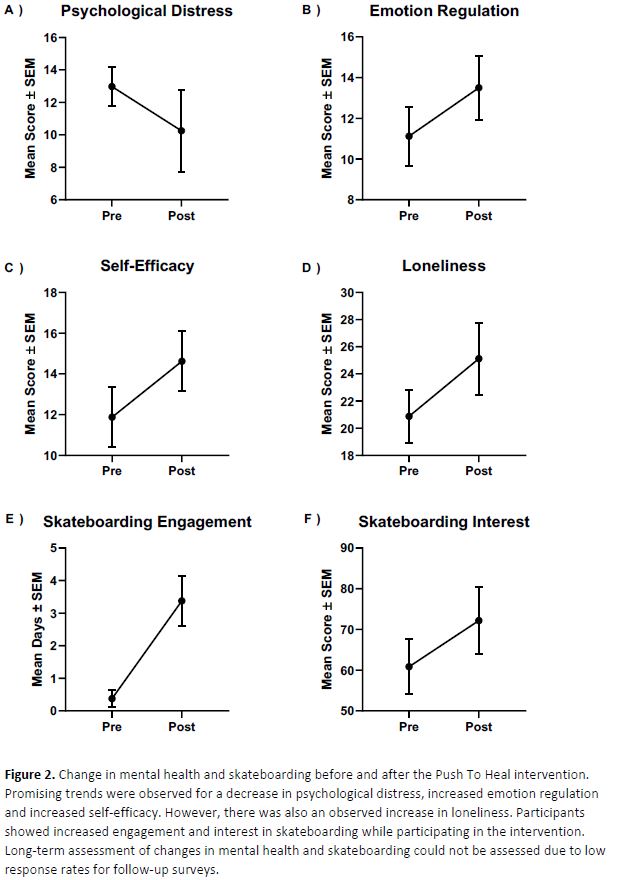

Demographic information was collected as part of the on-boarding process. Participants completed surveys pre-intervention, post-intervention, and at 2 and 3 month follow-ups. To assess any changes in physical activity, self-efficacy, emotion regulation, loneliness, and psychological distress, the following measures were utilized:

- International Physical Activity Questionnaire Short Form: to assess physical activity (Lee et al., 2011)

- Sport Engagement Questionnaire: adapted to assess interest and engagement in skateboarding (Guillen & Martinez-Alvarado, 2014)

- PROMIS General Self-Efficacy Short Form: to assess self-efficacy (PROMIS, 2017)

- PROMIS Managing Emotions Short Form: to assess emotional regulation (PROMIS, 2017)

- National Institutes of Health Toolbox Loneliness Fixed Form Age 8-17 v2.0: to assess loneliness (Salsman et al., 2013)

- Kessler Psychological Distress Scale: to assess psychological distress (Kessler et al., 2003)

Qualitative Data

Participants completed one-on-one interviews pre-intervention, and focus groups post-intervention. The interviews and focus groups assessed mental health needs, knowledge and interest in skateboarding, and impact on social, physical, and mental wellbeing. Notes were taken during the interviews, while focus groups were recorded. Data was transcribed and NVivo was used to support a thematic analysis.

Findings

Quantitative Data

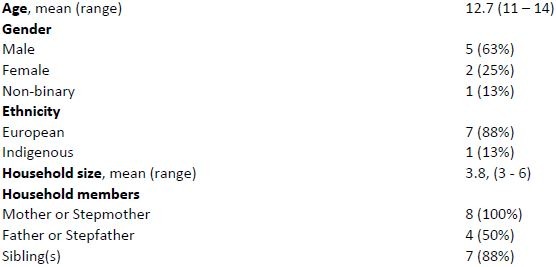

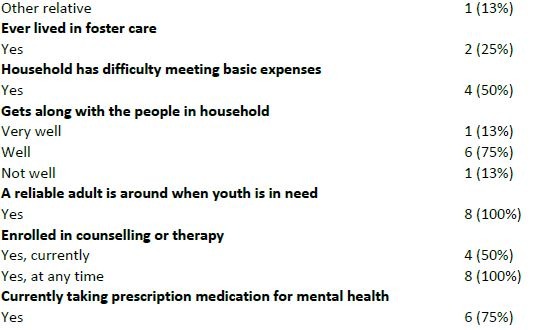

Demographics and household composition of participants are shown in Table 1. The program was successful in recruiting adolescents who have a history of mental health problems, many of whom also deal with socio-economic marginalization.

Table 1. Participant Demographics (n = 8)

Qualitative Data

Three broad themes were identified from the qualitative data: 1) skateboarding as a sense of freedom; 2) skateboarding as an activity to get them out of the house; and 3) a sense of building a community.

- Skateboarding as a Sense of Freedom

The first theme centered around skateboarding as a sense of freedom. Some participants reported that skateboarding allowed them to experience feelings of freedom, choice, and overcoming fear.

“Kind of like, you are free. You can do anything. You can be yourself.”

“You have a choice.”

“You just go out, do what you want.”

“Overcoming the fear of dropping into something.” - Skateboarding as an Activity to Get Them out of the House

The second theme focused on skateboarding as an activity that got them moving, mobile, out of the house, and away from their family.

“I think a lot of us probably live in toxic households.”

“You don’t have to hear your parents nag you as much to get out of the house.”

“It’s a good program to like get you out of the house.” - Skateboarding as Building a Community

Participants reported a sense of community and connection through the skateboarding program. Program participants indicated that they enjoyed skateboarding, especially when done with other youth, and expressed that they would likely skateboard with friends in the future.

“Make new friends.”

“A lot more fun to do it with other people. Have sessions and stuff.”

“Did it so I could not have so much social anxiety. People are gross.”

Limitations

It is important to note that this study took place during COVID-19 which presented unique challenges such as adhering to physical distancing protocols, isolation protocols if someone became sick, and other challenges that may have impacted participants and their families. Overall, limitations noted by the research team included: 1) delivery and design of surveys; 2) collecting data through interviews and focus groups; 3) lack of data collected from staff, family, and/or caregivers; and 4) full evaluation of program efficacy.

- Delivery and Design of Surveys: Participants had challenges completing surveys on-line. Some participants identified needing help to read the surveys, while others did not have access to a computer to complete the surveys. Participants appeared to have issues accurately reporting their level of exercise using the International Physical Activity Questionnaire. Furthermore, this study adapted the Sport Engagement Questionnaire to assess skateboarding engagement; however, the survey was designed for professional adult athletes and was therefore not appropriate for participants.

- Collecting Data Through Interviews and Focus Groups: Interviews and focus groups with participants was challenging. Participants provided short, vague, and often conflicting answers to the questions they were asked. This could have been due to: 1) not knowing the interviewer and therefore, not establishing a relationship of trust to share openly and honestly; 2) participants may not have felt comfortable answering questions within a focus group setting for confidentiality reasons; or 3) focus groups may not have been appropriate for these participants.

- Lack of Data Collected from Staff, Family, and/or Caregivers: Perspectives from Push To Heal staff, family members/caregivers, or other individuals associated with participants were not identified as a data collection method in the ethics application and therefore, were not captured in the evaluation of the study. This ultimately resulted in not having a complete understanding from multiple perspectives of the impact the intervention may have been having on participants.

- Rigorous Evaluation of Program Efficacy: A rigorous statistical evaluation of program efficacy was restricted for numerous reasons including a short timeline from recruitment to program start date, very small sample, holiday and staffing issues, missing data from post intervention follow-ups, difficulties with on-going engagement with youth post intervention, not having a specific point of contact to ensure follow-ups could be completed, and a lack of control group to determine if the intervention did in fact have an impact on youth mental health.

Recommendations

The following recommendations align with the limitations noted in the previous section.

Delivery and Design of Surveys

- Administer surveys in-person, not on-line. This would:

- allow participants to ask questions if they didn’t understand a survey

- ensure reading levels aren’t a barrier to completing the survey

- ensure participants aren’t excluded from participating because of a lack of access to technology

- Use alternative surveys to assess overall physical activity and time spent skateboarding.]

- If validated measures cannot be found, the research team could simply ask participants to keep track of how much time they have spent doing any physical activity during the past week, and what that activity was.

Collecting Data Through Interviews and Focus Groups

- Engage participants in interviews rather than focus groups.

- Interviews with participants should be done with someone with whom participants have a relationship and have built a level of trust with. This could be done with a staff member at Hull Services who is not associated with the project but who has established trust with the participant. A trusting relationship is more important than having the skills to interview and thus, the research team could provide training for this person.

Lack of Data Collected from Staff, Family and/or Caregivers

- Conduct interviews and/or focus groups with Push To Heal program staff, other Hull Services staff members, and parents and/or caregivers.

- These interviews and focus groups could facilitate discussion and dialogue around the intervention and what seems to be working, what isn’t working, and any other observations made that aren’t being captured through survey data.

Rigorous Evaluation of Program Efficacy

- Utilize a control group that does not receive the intervention.

- Given that participants were already receiving services for their mental health and understanding that youth mental health is constantly in flux, a proper assessment of program efficacy would require a control group that did not receive the intervention. A control group would allow for a proper assessment of program efficacy.

Conclusion

Future research is warranted as the findings from this study support the anecdotal evidence from Hull Services that skateboarding may have a positive impact on youth mental health. Incorporating the recommendations into the next phase of piloting the Push To Heal program would allow for a deeper statistical analysis and understanding of the impact of the intervention from multiple perspectives for pushing this important work forward.

Research Team

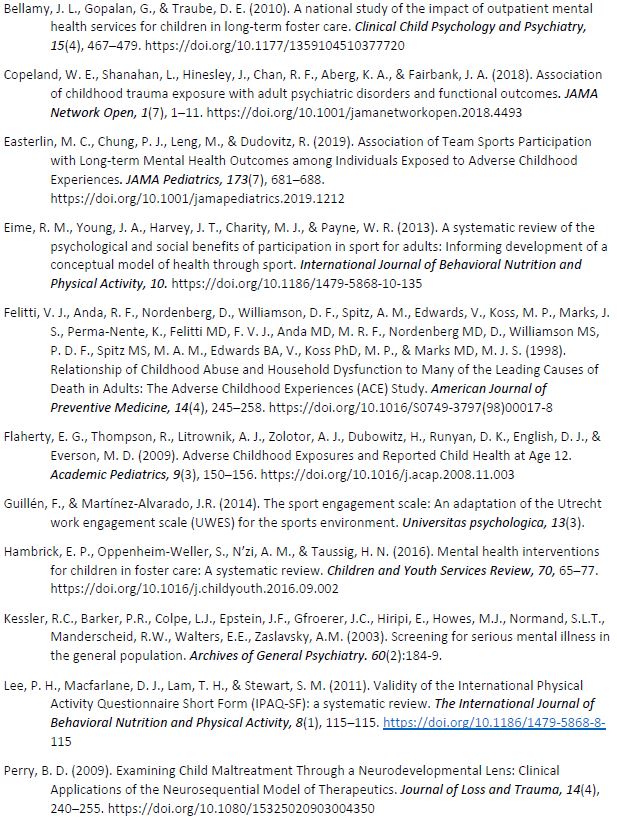

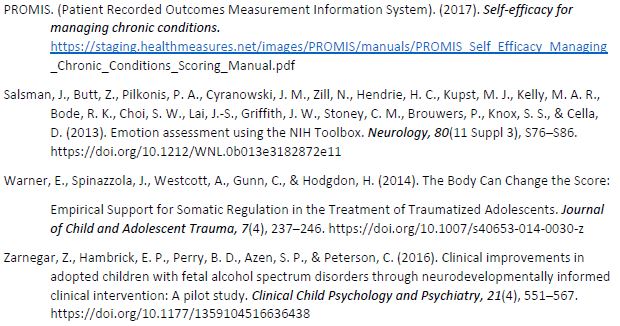

References